PREFACE

As the year 2016 drew to a close, we faced what UN Emergency Relief Coordinator Stephen O’Brien would tell the Security Council was the “largest humanitarian crisis since the creation of the United Nations”. Much though of this food-security emergency was the result of conflict – in Yemen, Somalia and South Sudan, three countries he had just visited.

But also on Mr O’Brien’s acute list was Kenya, with millions of people affected. Attribution scientists later concluded the drought there was actually fairly frequent and that rising temperatures may have added to the problem.

With a slightly different humanitarian geography in mind, the IFRC said the lives of nearly 20 million people were at risk in the Horn of Africa and Nigeria in “one of the worst hunger crises in recent history”. This would be repeated, our colleagues argued, without “concerted efforts to build resilience on the continent”.

On the ground in the most vulnerable parts of the world, 2016 did not end well; we call it ‘a year of hunger’, and it was climate – both climate change and variability as much as conflict – that inflicted much of this suffering. The year started with the remains of the strong 2015–16 El Niño, transitioning to a La Niña that helped explain the drought in Somalia, for example.

Ironically, at the end of an exceptionally engaged and busy year for us, we allowed ourselves a moment of optimism as we believed we saw international action on climate moving forward; perhaps even gaining momentum.

The historic Paris agreement was not only ratified quicker than hoped, it also crossed the ‘55-55’ threshold that meant the UN was able to announce it was coming into force faster than anyone foresaw. The first round of high-level climate negotiations after Paris, COP 22 in the Marrakech, straddling the US presidential election, ended without major setback.

We argued that 2016 saw one of the first real examples of international action bridging humanitarian, development and climate work, in the form of the UN special envoys on El Niño and climate who presented for a blueprint highlighting the need to invest on a much larger scale ahead of predictable crises.

As well as ever-closer collaboration with the IFRC secretariat, we also intensified collaboration with the ICRC, including a presentation to Geneva staff on the Paris agreement and the way we believe climate affects the International Committee’s work.

In fact, in 2017 we are looking further ahead still, helping to build scientific foundations for climate decisions for many years to come. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), for example, is commencing work on its special report on ‘1.5 degrees’ as well as its next full assessment cycle, the sixth.

In the context of the immense humanitarian challenges the world faced in 2016 and new ones ahead, we are proud of the Climate Centre’s small but significant contributions. We thank all our partners and look forward to continued joint efforts to better manage the rising risks.

by Ed Nijpels and Maarten van Aalst

The year started with the remains of the strong 2015–16 El Niño, transitioning to a La Niña, both responsible for significant humanitarian impacts. These included the El Niño-related drought in Southern Africa and parts of the Horn of Africa, followed by droughts in other areas of the Horn and the crisis in Somalia, affected by La Niña.

In 2016, with support from the UK Department for International Development (DFID), the Climate Centre conducted research to determine whether El Niño forecasts prompted early actions and reduced the need for additional response in Zambia, Somalia, Kenya, Ethiopia and Malawi.

Organizations generally found the international El Niño forecast to be credible, but scaled-down forecasts were regarded as more useful for planning. Most organizations used the El Niño forecasts to update their contingency plans, but implementation of these plans was hindered by lack of funds. Strong coordination, availability and flexibility of funding mechanisms, access to skilled intermediaries to interpret the forecasts, and political will all enabled the use of El Niño forecasts.

Organizations from all five countries highlighted the need for flexibility in funding and programming as key.

Our research concluded that humanitarian organizations used El Niño forecasts to trigger early action, and humanitarians see triggers and standard operating procedures as a way of streamlining response to forecasts.

In November at the UN climate talks in Marrakech, the Climate Centre spoke for the IFRC informally supporting the developing UN ‘blueprint for action’ on El Niño, and applauding the world body for “bringing the humanitarian and development dimensions of resilience to the heart of the climate negotiations…in Marrakech”.

Patricia Espinosa, UNFCCC Executive Secretary, officiating at COP 22, said the entry into force of the Paris agreement was a cause both for celebration and a timely reminder of the high expectations raised. “No politician or citizen, no business manager or investor can doubt that the transformation to a low-emission, resilient society and economy is the singular determination of the community of nations,” she said.

At the end of the climate talks,the IFRC welcomed the commitment by governments to implement Paris and looked forward to seeing it translated into action. The Climate Centre also took part in the IFRC’s principal side-event at COP 22 on devolving climate finance, jointly organized with the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED).

The 2016 Development & Climate Days brought many COP participants together to explore how to bridge the global ambition of the Paris agreement with local action. More than 300 people attended the two-day event whose theme was Global ambition. Local action. Climate resilience for all, and which also for the first time included the private sector.

D&C Days is well known for encouraging innovative thinking and outside-the-box sessions, and last year the Climate Centre introduced new games, a flash mob on heatwave risks by young volunteers of the Moroccan Red Crescent, a ‘Taste the Change’ session, and a virtual-reality experience to enable people to experience the complexities of climate decisions.

The Climate Centre took an active part in the ‘loss and damage’ discussions which mainly dealt with the implementation of the two-year work-plan of the Warsaw International Mechanism (WIM). We believe the needs of the most vulnerable groups were considered and addressed by the WIM executive partly as a result of this engagement.

A key Climate Centre contribution was at a specialist financial committee in Manila where we shared experiences and learning on managing climate risks through social protection and FbF. We also successfully advocated for the IFRC to be included in a global task force on displacement that was having its first meeting in 2017.

PfR successfully finalized inception for its next phase in 2016. Building on five years’ experience, the alliance is now focusing on strengthening National Societies and civil society in Ethiopia, Guatemala, Haiti, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Mali, South Sudan, Philippines and Uganda. (Nicaragua has been replaced by South Sudan and Haiti in the new phase.)

Among snapshots from Climate Centre engagement in several countries and regions is work in Uganda, where two districts have now selected the dissemination of weather forecast information as one of their key priorities for 2017–18.

In the Philippines, the integrated approach is being advocated at different levels, with the Philippine Red Cross at the national level, for example, through inputs into planned legislation, while at the local level it’s being included in government plans on climate action.

In India and Mauritius, the Climate Centre together with PfR agencies and IFRC delegations have taken a very active role in regional platforms on risk reduction, influencing thematic events linked to risk management and community resilience.

Among the global-level highlights of 2016 was our engagement with the UN Secretary-General’s ‘A2R’ initiative on resilience, where we have worked with the UN envoys on El Niño and climate, Mary Robinson and Macharia Kamau.

A substantial number of civil society organizations came together to discuss how to build resilience around the world as BRACED gathered for three days of learning in Dakar, Senegal, in February.

Twenty webinars and discussion forums were offered to BRACED partners and the public, exploring topics from using climate information to sharing experience from communities and policy-makers.

We published fact sheets to support innovative approaches to learning and implementation ranging from ‘forum theatre’ and ‘learning marketplaces’ through techniques for reflection and exchanging knowledge. Lessons on how learning in consortia is facilitated are already being transferred to other contexts such as PfR. Through collaborations with journalists, scientists and experts, the team explored how extreme events – including intense rainfall in Nepal, Senegal and Kenya and drought in Ethiopia – affected people and their stories of resilience that emerged. Lessons have been widely shared through the media, academic papers and webinars.

We facilitated knowledge and learning on new ways of increasing resilience at scale through social protection – potentially a vital instrument for addressing climate risks though sustainable systems that enhance both humanitarian action and poverty reduction.

In 2016, the WWA initiative joined with the Climate and Development Knowledge Network (CDKN) to launch the ‘Raising Risk Awareness’ project that would focus on attribution in East Africa and South Asia. The Climate Centre convened stakeholders, including National Societies and the IFRC, in India, Ethiopia, and Kenya to build the capacity of scientists and decision-makers to conduct attribution studies.

Human-caused climate change was found to have played an important role in the heavy rains that affected France near the end of May, increasing the chance of such an event by at least 40 per cent. In Germany the same weather system dropped large amounts of rain in a very short period on mountainous terrain causing devastating flash floods, but the methods used to assess this did not provide consistent results.

On 19 May, India experienced an all-time record high temperature of 51°C in Phalodi, Rajasthan, but an attribution analysis did not find that human-induced climate change played a role, probably due to the ‘masking effect’ of aerosols on warming.

Kenya’s drought emergency left at least 2 million people in need of food assistance. Scientists found that this type of event actually occurs about twice a decade in the areas studied, but the current drought continued into 2017 so may yet be found to have been statistically more extreme.

The American Red Cross called the 2016 flooding in Louisiana the worst natural disaster in the US since Hurricane Sandy,and WWA scientists partnering with government found human-caused warming increased the chances of the torrential rains that caused it by at least 40 per cent.

Since 2015, the Danish Red Cross, the IFRC and the Climate Centre have together provided support to the National Societies of Armenia, Georgia, Kenya, Malawi and Nepal, to engage with their governments in the development of National Adaptation Plans to ensure the adaptation needs of the most vulnerable people are considered.

With this project ending in 2017, the focus was on synthesizing the lessons learned from the five different countries at a writeshop alongside COP 22 in Marrakech that produced a case-study publication.

The Climate Centre also worked with National Societies to conduct local capacity building events, including in-house staff training with the Nepal and Georgia Red Cross, advocacy training with the Armenia Red Cross, and a training workshop for Europe and Central Asia.

We have created new tools on emerging themes that now include preparedness for urban floods and social protection.These and others were used in capacity-building initiatives around the world, including a training session organized with the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) in West Africa and a workshop that brought together humanitarians and ‘facilitation champions’ of the Applied Improvisation Network.

A World Bank annual retreat involved 150 senior managers in playing our ‘Decisions for the Decade’ game to explore climate risk and uncertainty.

In the Asia-Pacific region, our tools were used during high-level regional meetings including the Asian Ministerial Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction in Delhi. They also helped shape workshops at the local level – on climate action in the Philippines, for example.

The UN Food and Agriculture Organization commissioned a game on ‘shock-responsive social protection’, played at the UN climate talks in Marrakech.

The Climate Centre teamed up with the Madagascar Red Cross to adapt climate games to local context to enable communities to simulate climate impacts in a safe environment and develop their own solutions. At least 1,300 people took part while 80 Red Cross staff and volunteers facilitated.

Together with UNICEF and other partners we have created ‘Handwashing with Ananse’, an educational approach which engages children in school through storytelling, songs, dance, acting and play. Ernest Nyame of the Ghana Red Cross became an IFRC ‘global innovation pioneer’ as part of this and is now planning to expand the work to reach 20,000 children.

Together with Plan International, the Philippine Red Cross and other partners, we have also created Y-Adapt – ‘Youth action on developing adaptation plans for tomorrow’ – a curriculum consisting of games and play. This helps young people to understand climate change and to take practical action to adapt to the changing climate in their community.

The year 2016 also saw new areas of innovation by the Climate Centre.

Blending interactivity with innovative approaches to data visualization in virtual reality, the Climate Centre brought FbF to a new level. Based on historical data on flood impacts as depicted in a virtual data sculpture, players establish a danger level so that when flood risks emerge, the FbF system automatically triggers funding for preventive measures.

During a seemingly normal session at the UN climate talks in Marrakech, participants sensed that something unusual was about to happen. A disruptive yet peaceful group of people rush in and start a performance that blends music, movement and message. A simulated heatwave had arrived, and with it inspiration on how to manage the growing threat of extreme temperatures to city-dwellers.

Another new way to communicate risk is ‘edible data’. With culinary and visual arts as its medium, data cuisine sessions brought to D&C Days a sensory exploration of climate data and its implications for humanity.

FINANCE

The Climate Centre – an independent foundation under Dutch law – remains grateful to its hosts, the Netherlands Red Cross in The Hague, which every years assists us with HR, legal and financial expertise.

In 2016, most of the Climate Centre’s income came from the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the UK Department for International Development, and the German and Norwegian Red Cross and their governments. We were also supported by:

American Red Cross

British Red Cross

Danish Red Cross

German Red Cross

Netherlands Red Cross

New Zealand Red Cross

Norwegian Red Cross

Swiss Red Cross.

Other contributors were the Norwegian University of Life Sciences, the World Meteorological Organization, IFAD, CDKN, UTC, the Natural Environment Research Council, the World Bank, and the European Commission.

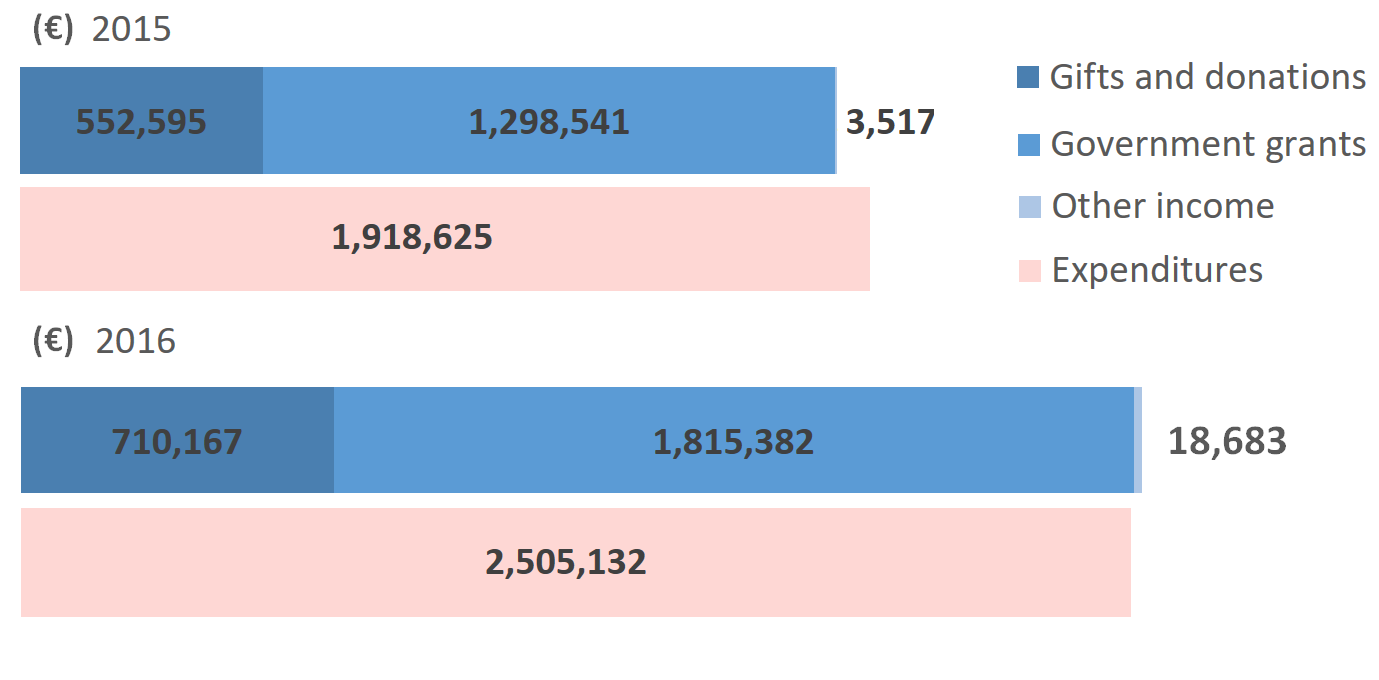

Below an overview of our income and expenditure for 2016, with the numbers from 2015 added for reference.

The positive balance from 2016 has gone to our mission reserve. More detailed information can be found in the full Annual Report 2016.

We thank our supporters for their generosity and their collaboration.